Explore how anxiety can show up in your life, work, and relationships

Read on

What is Mindbody Science?

Avoiding wormholes and giving the kid sister a break

Artist's illustration of a supermassive black hole in the middle of the ultradense galaxy M60-UCD1. Credit: NASA and ESA.

My Ultimate Stress Relief Cheat Sheets, published last July, kicked off with a timeline of answers to the question:

Why didn’t I know that anxiety was behind my pain?

2015: I don’t care why I didn’t know. I want to know why the therapists I saw didn’t know.

2017: Seems like, in the field of mental health, you need to know what’s wrong with you for people to be able to help you. At least I have Lexapro now.

2019: I guess I hid it so well that I unintentionally hid it from myself? I still have physical symptoms. I continue to be grateful for Lexapro, which helps me turn down the thermostat on my internal environment, especially on anxious mornings.

2021: I am still really sick—nausea, muscle aches, migraines, lightheadedness. Is anxiety connected to the physical pain I am in? I still don’t get it. COVID hasn’t helped.

2023: After a year spent in bed, something finally helped: I had a hysterectomy. I’m grateful to see a decrease in my physical symptoms, but I am still in pain. I don’t know what to do next. I suspect my nervous system plays a role here.

2024: I finally get it —I have spent a lifetime in a state of nervous system dysregulation. I believe I can improve my physical and mental health by regulating my nervous system. My pain is diminishing. It’s a daily practice, but I am healing.

In this article, I’ll be digging into the mechanism that, in the last two years, has helped me change my relationship with both pain and anxiety to the point where I’m no longer even asking that question about anxiety (because I no longer care). Here’s what my new timeline of thinking sounds like:

How do my thoughts, beliefs, and emotions affect my life?

2015: (scrunching forehead) Well, I just learned that an anxiety disorder appears to be at the root of my issue, so I guess in my case they are negatively affecting my life.

2017: I’ve been writing about the perils of overthinking for two years and have learned that without conscious effort to change, my thoughts, beliefs, and emotions will negatively impact my life.

2019: Some of us need medication, meditation, and communication to successfully navigate our thoughts, beliefs, and emotions.

2021: (forefinger raised) I am reading a lot of books and learning a lot about emotions. Want me to tell you some stuff? Let’s go.

Early 2023: I finally believe I can heal my mind and body. I have no idea how I will do it.

Late 2023: Wait, what’s the role of the nervous system here?

Early 2024: (highligher in hand) Out of sheer desperation I’ve discovered Sarah Warren’s Pain Relief Secret and begun her online clinical somatics program. My mind is being blown by what I’m experiencing.

Mid 2024: (Headphones on) I’m completely bought in that the nervous system is the answer to the question listed above. I’m listening to Sarno acolyte Nicole Sach’s podcast, learning about pain reprocessing (described here as the third leg of my tripod of healing).

Late 2024: Every day I am seeing how thoughts, beliefs, and emotions show up in my body, which, in turn, affects every part of my life. I’m learning to regulate my nervous system in order to be able to show up for people I love (and myself).

Early 2025: I’m so lucky to live in a time where I can live the answer thanks to the work of early mindbody science pioneers.1

“All of this is fine and good, Meredith,” you might be saying to yourself, “But I still don’t understand exactly what mindbody science is. It barely comes up when I google it. Why is that?”2

What is Mindbody Science?

Great question, skeptical reader, and one that quickly leads us down a deep philosophical wormhole.3 When it comes to this question, it’s easy to get real big, real fast. That’s my theory for why it barely comes up when you google it. No one — including me!—wants to wade into open-ended questions on the nature of consciousness online. We all know that once you’ve opened that can of worms, wormholes will follow.

So I’ll just share that in 1641, in a turning point for Western philosophy, Rene Descartes introduced the concept of Mind-Body Dualism. This foundational understanding of the mind and physical body as separate entities shaped much of the thinking that followed it4 including, sadly, modern medical practice.5

From Biomedical to Biopsychosocial

Biomedical science is that confident guy who strides forward to shake your hand, clear about who he is and what he’s doing.

Nice to meet you, I’m biomedical science.

Nice to meet you, I’m biomedical science.

Biomedical science is the study of anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, and statistics to understand how the body's organs, cells, and systems function. This is what most people think of when we talk about medicine and the physical body, and for good reason. Biomedical science is what led humans to the discovery of penicillin, anesthesia, medical imaging, germ theory, and the discovery of the DNA structure. Biomedical science, with his straight teeth and bright smile, has the confidence of a winner.

Mindbody science, on the other hand, is a bit more complex.

Oh hey, nice to meet you. Sorry, I’m distracted. Got a lot going on over here. I’m mindbody science.

Oh hey, nice to meet you. Sorry, I’m distracted. Got a lot going on over here. I’m mindbody science.

Biopsychosocial medicine, the broader model that mindbody science falls under, focuses on the interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors in the study of health and illness. It encompasses various disciplines inc neuroscience and psychoneuroimmunology, or the study of the interaction between psychological factors and the nervous and immune systems. For example, the biopsychosocial model might examine how a psychological factor like stress can influence a biological factor like cardiovascular disease, or how a social factor like support can affect recovery from illness.

An often-overlooked subset of biopsychosocial medicine, mindbody science focuses on improving wellbeing by studying how thoughts and emotions influence physical health. Mindbody scientific research, for example, might investigate how mindfulness practices affect immune function or how stress reduction techniques can impact cardiovascular health.

The obstacles to widespread adoption of mindbody science are many. This July 2005 paper, Barriers to the Integration of Mind-Body Medicine, explored those obstacles in medical training. Physicians, residents, and medical students listed the following reasons that mindbody science isn’t widely embraced:

the common perception that psychosocial factors are beyond a doctor’s capacity to control

the common perception that patients do not want to address their psychosocial/lifestyle issues

the cultural beliefs (perhaps rooted in Cartesian dualism?) that addressing psychosocial issues is not within the purview of physicians

the lack of knowledge about existing research due to insufficient monetary incentives

a larger cultural ethos that favors the “quick-fix” over the more difficult task of examining the role of psychosocial factors

In other words, mindbody science is a kid sister who’s shouting to be heard, wanting to be appreciated for her unique skills while being overshadowed by her big brother, biomedical science.

What’s the good news?

The good news is that the tides are turning. I’m not the only person getting fascinated by the healing potential for mindbody science at scale. In the same way that I got a lower back tattoo two years before everyone else did,6 I am convinced that the next few years will see an explosion of interest in mindbody science.7 I’ll be the first one in line to cheer new discoveries while working to share them with you all here in my newsletter. So if you’ve haven’t subscribed yet…

What comes to mind when you hear the words “mindbody science”? Share in the comments below!

Footnotes

A particular thank you to those pioneers in the study of somatics, polyvagal theory, EMDR therapy, and pain reprocessing.

I have so much love for my skeptical readers because I. am. you.

I opened this post with an artist’s rendering of a black hole. Black holes are real. They are made of strong gravity that nothing, not even light, can escape. A wormhole, meanwhile, is a hypothetical tunnel that connects two different points in space. It is not real.

Note: After reading this piece, a smart fellow Voyager wrote me to say that while it's easy to center Descartes as the launching pad of mind/body dualism, it's important to acknowledge the role of technological changes that enabled him to do so. He says, “The moveable type printing press, for example, enabled the extension of human will far beyond the reach of the human hand, as well as the inclination towards a need for refined measurement, which did much more to set the stage for Descartes than Descartes lighting a fuse. I am not confident that a simple philosophical shift restores something in a significant way when so much of the modern world is built on these foundations.” Thank you, friend, for making sure this piece acknowledges the complexity of our shared human history.

In this paper, Mind-body Dualism: A critique from a Health Perspective, clinical psychologist Dr Neeta Mehta argues that Cartesian dualism has led to a crisis in modern medical practice due to biological reductionism.

Let’s just throw into a footnote that once it hit mainstream it was called a tramp stamp, shall we? Doesn’t really need to go into the main body of the text, does it?

Another reason to trust me: I was one of the first people to start writing about mental health in 2015, just a few years before it started to get trendy. Mark my words, I’m always just one tiny step ahead.

Somatic Meditation

What do these words even mean?

The deeper I get into mindbody science, the more I am blown away by what it has to teach me. In this newsletter I’ll dig into an approach to meditation I never really understood until now. I’ll share my perspective on what makes it powerful and explore how it differs from my traditional longstanding meditation practice. 1

First, the groundwork. A basic search of word “somatic,” or, “relating to the soma,” will lead you to the Oxford English Dictionary definition where you will learn that “soma” is a fermented ritualistic intoxicant (aka a Vedic version of Kiddush or Communion).

As truly fun as that drink sounds (and it does sound fun), I prefer Thomas Hanna’s2 definition of soma as described in his groundbreaking book: “the body experienced from within, emphasizing the mind-body connection and the body as a living, self-aware process.”

In other words, somatics is the study of how humans experience their bodies from within. This is a more nuanced take than I understood a few years ago, when I thought, like most people do, that our bodies are external objects moving through space, and that somatic simply meant “of the body.”

It’s an important distinction, and it relates to why somatic meditation has been misunderstood and underexplored. If your mindset is “a meditation for a body moving in space,” then somatic meditation is a pretty simple thing. In fact, as part of my early work on How We Feel in 2021, I produced this video on walking meditation:

If you had asked me then, that video ^^ is what I would have pointed to as an example of somatic meditation. And it is! But I believe it is missing some of the most important features of “the body experienced from within” kind of somatic mediation that Hanna describes. To understand what I mean, take a look at this popular Youtube video on somatic mediation hosted by Sukie Baxter:

Note that in the past, I may have written off Sukie’s video before watching it due to a misunderstanding of what trauma actually is,3 but I encourage you to avoid that mistake. That said, most of you will not want to spend the 13 minutes it takes to watch the video, and as a consummate fast newsletter skimmer, I support that. Here’s a breakdown for all of you fast skimming readers:

In both traditional and somatic mediation, you are…

Building your awareness of the present moment

Creating space between you and your thoughts

Grounding your body in the present moment (e.g. “Notice the ground underneath your feet, the cushion underneath you”)

In somatic meditation, however, you are also…

Keeping your eyes and ears open in order to engage with your environment

Using your surroundings for intentional nervous system regulation4

Building a psychological bridge between the outside world and your inner world5

Grounding your body through intentional, slow movement (e.g. “Wiggle your toes and feel the carpet underneath them”) which gives your brain more sensory information that allows it to recalibrate at an unconscious level

Doing a very lightweight version of the kind of movement found in EMDR therapy6 by allowing your eyes to move bilaterally

Bringing attention to the felt experience of the body without lingering on pain7

Expanding your sensory inputs through bilateral listening (7:20 in Sukie’s video)

Orienting your nervous system to the present moment which allows it to discharge the stored stress you aren’t even consciously aware of

It’s taken me about a year to really understand the power of somatic meditation, so if this all feels a bit confusing, just know you are not alone. The information I have shared in this newsletter is very hard won — there isn’t much information I could find online that talks about this topic in this way. That’s even more a reason I wanted to share this with you all today. I’m sure this topic will come up more in future newsletter, but for now I’m glad to have shared the basics, and hope it will inspire you to give this new approach a try.

If you do end up trying somatic meditation, I’d love to hear how it worked for you. Share in the comments below!

Footnotes from original Substack piece

Here’s a very short newsletter I wrote in 2017 inspired by my daily Headspace practice. From 2015-2018 I meditated for at least 20 minutes most days, graduating from guided mediation on Headspace to a simple sitting practice with my own visualizations — a gong to signal every ten minutes that passes — using Insight Timer.

Thomas Louis Hanna (November 21, 1928 – July 29, 1990) was a philosophy professor and movement theorist who coined the term somatics in 1976. You can learn more about him in this interview I did with Sarah Warren, the founder of the Clinical Somatics practice I love.

This newsletter one year ago: “I never thought of myself as someone who was in the “trauma” category. Trauma is a very serious word. I never thought my small daily struggles rose to the level of “somatic trauma response. I now know that many different things can lead to lower case “T” trauma response,” or, as Dr. Gabor Maté states, “Trauma is not what happens to you, it's what happens inside you as a result of what happened to you.”

Allowing your eyes to land on something that catches your attention, then spending time taking in details helps move your nervous system from sympathetic to parasympathetic, fight or flight to rest and digest.In her video, Sukie asks, “Notice the movement of your breath, the rhythm of your heartbeat. Are you able to attend to that feeling inside your body while maintaining that connection to your external environment?” This is intentional conscious bridge-building between what is happening inside vs outside.

In her video, Sukie asks, “Notice the movement of your breath, the rhythm of your heartbeat. Are you able to attend to that feeling inside your body while maintaining that connection to your external environment?” This is intentional conscious bridge-building between what is happening inside vs outside.

I’m saying this even though I know (as you’ll see in the EMDR piece I link to) that there is no consensus around what makes EMDR work and some people will say, for example, “it is not the bilateral stimulation that works in EMDR, but dual attention accompanied by physical stimulation.”

This helps your primitive brain (which loves to focus on negative feelings) to understand that there are always a wide variety of sensations happening inside our bodies at all times, allowing the space for that variety.

What is Polyvagal Theory?

Polyvagal theory often uses the metaphor of a ladder to describe the autonomic nervous system. This photo is by Xin.

Despite the fact that it floated around me for years, I never paid attention to the word “polyvagal.” My (incorrect) assumption was that if polyvagal theory really worked, I’d hear about it via word of mouth. That changeI’ve begrudgingly accepted that I am that word of mouth.

As this Wikipedia entry on polyvagal theory shows, this is a new and emerging field of science. Wiki editors are adding new links to impassioned scholarly articles on all sides of the debate as we speak. Instead of hand-wringing about this, I’m focusing on how polyvagal theory helps me understand which actions to take depending on the state my nervous system is in. I’ve needed this for a long time.

Polyvagal is a new understanding of how the autonomic nervous system regulates behavior to keep us safe pioneered by Stephen Porges in 1994. In the same way that critical somatics helped me establish a daily foundational practice for nervous system regulation, polyvagal theory has given me in-the-moment techniques that help me regulate. It also provides me a framework for understanding how my nervous system works and what it needs to function properly.

Rundown of the nervous system “states” as described by Stephen Porges

Polyvagal theory has helped me understand how my nervous system tries to protect me by changing states in response to what’s happening. I can now recognize what being stuck in a hyper- or hypo-aroused state feels like (again, if you don’t know what this means, you were me before learning about this theory). I’ve learned which polyvagal tools to use to build my tolerance for inevitable daily stressors. And since polyvagal emphasizes the importance of co-regulation, or how people interact with each other to manage emotions, it’s led me to invest more in personal relationships as an important path to improvement.

Learn more

Where Did Weighted Blankets Come From, Anyway?

A Q&A with Keith Zivalich

Keith Zivalich with Pugsly, the Beanie Baby that led him to his “aha” moment in 1997.

Bevoya: Can you tell us about your background -- where did you grow up? where do you live now? What do you do for a living? And a little about your own mental health journey, if you have a journey to share?

Keith: I grew up in Los Angeles. Now I live with my family in Valencia, CA, a suburb outside of LA. Since, 2015, my primary source of income is through running a small family e-commerce business making and selling The Magic Weighted Blanket. I don’t really have much of a mental health journey other than recently self-diagnosing myself as a highly sensitive person, which is not a disorder but more of a personality trait. Not sure it had anything to do with me inventing the weighted blanket, but I do know I instantly felt a calming sensation the first time my daughter placed her Beanie Baby on my shoulder, which was the inspiration for the weighted blanket.

Bevoya: How did you start exploring weighted blankets? What was happening in the world at that time and what led to your insights?

An early prototype of the “bean blanket.”

Keith: In 1997, our family had just moved back home from Boise, Idaho where I was working for an ad agency. One day, my daughter placed a Beanie Baby on my shoulder and I noticed how it hugged me. My first thought was to imagine a blanket filled with these little beans. It would be “the blanket that hugs you back,” which is now our registered trademark. I asked my wife to make a child size prototype to show around to our neighbors with kids. No one liked it. It was too heavy. I remembered a friend of ours who is a special needs teacher telling me that she used to hug the kids with autism and sensory processing disorder in her class to calm them down. I gave her the prototype to try out. She came back the next day saying she needed more. From that moment on, I knew weighted blankets were going to be huge. I found a manufacturer here in Los Angeles and started making them. We called our new business The Original Beanie Blanket Company but Ty Corporation, the maker of the Beanie Babies, sent us a Cease and Desist letter, so we called it the Original Bean Blanket Company. That’s our legal name to this day. We sold our first blanket in 1998 to a friend we made in Boise, Idaho.

Bevoya: In the past decade or so weighted blankets have become incredibly popular. As someone who has watched the marketing cycle unfold, what has surprised you about the popularity of weighted blankets?

Keith: Honestly, I was not surprised by their popularity. What did surprise me was that it took so long. Knowing that we had a market within the autism and sensory processing disorder communities, we started marketing our weighted blankets to OTs in 1998. Around that time, I had applied for a patent on my own for the design of a weighted blanket, but it was denied. By the early 2000s, as OTs started to get the word out about weighted blankets, there were a couple of moms with special needs kids who also started making and selling them. Slowly, over the next decade, weighted blankets remained a cottage industry, but there was growing awareness. By around 2014, the mass media started catching on. We were featured in Forbes, Cosmopolitan, Dr. Oz, Wall Street Journal, USA Today and others. It was around that time, I was able to quit my regular job and focus on the family business. Then, in 2017, we were interviewed by Time Magazine for their 2017 invention of the year award. After hearing about our journey from inventing a new product and becoming a leader in a niche community, we were sure we would be featured. But alas, no. The award went to the Gravity Weighted Blanket which had broken the record on Kickstarter for raising the most money for a start up. By that time, we had been in business for almost 20 years. With the award, they acknowledged that Gravity did not invent the weighted blanket, but that they brought it to the mass market. From 2017 on, weighted blankets exploded, as did our business. But with that media attention came an outpouring of competition, now obtaining their weighted blankets from China, like Gravity did, and the prices for weighted blankets dropped to a level that has made it very hard for a US manufacturer like us to compete. So now, instead of just trying to sell The Magic Weighted Blanket, I am trying to sell the one person who has been there all along, The Weighted Blanket Guy.

Keith: It wasn't like one day I woke up and thought, "Hey, I should be the weighted blanket guy." It has been something people have been calling me for many, many years. From day one, when we started a niche company and all the way through the explosion of weighted blanket's popularity, I have always answered customer phone calls and emails, and when I introduce myself, I very often heard people say with shocked surprise, "You're the weighted blanket guy." And one of the things about being a small family business, you pretty much have to do it all, and that includes building your brand. I've spent 26 years building the Magic Blanket brand and thought it was time to put myself out there as the guy who started the weighted blanket phenomenon. And although I don't like him, it has worked wonders for The Pillow Guy. The goal is not to necessarily promote my brand, but to promote me, my story and the knowledge I have gained by being consumed with all things weighted blankets so I can help bring a little calm and comfort into people's lives.

Bevoya: What do you wish more people knew about weighted blankets? What do you think companies get wrong when they try to sell them?

Keith: I wish people knew that weighted blankets have been bringing calm and comfort to people for a long time and that it is not because of the media hype. That media hype has turned weighted blankets into a get rich quick scheme by many start ups. They buy cheaply made and priced blankets from outside the US, make a lot of money, sell the company and look for the next media darling. In the meantime, we have loyal customers who have found a holistic remedy to their anxiety and sleeplessness and then tell their friends and we eke out an existence. Weighted blankets work. There is science behind it with a long legacy of helping people. That is the story the media giants should be telling. So the Weighted Blanket Guy is telling it.

What these companies get wrong based on customer feedback is that these companies are selling one size for both men and women – a 48x72. Most of the factories in China mass produce these as a standard size. There are two drawbacks to this size. 1) 48 inches is often too wide for most women. It spreads the weight out too much so the person is actually under less of the compressive weight, which is where the magic happens. 2) 72 inches is too short for most men. All blankets have a tendency to pull up. A 72 inch blanket is going to pull up over a taller person’s feet.

Keith with his family in the early years

Bevoya: Do you have a favorite type of weighted blanket? What should consumers look out for when trying to choose one?

Keith: I have been sleeping with same Charcoal Grey Chenille 20 pound blanket for going on 10 years. Chenille is our most popular because it is super soft and durable. There are several things consumers should look for:

Get the blanket to fit the body, not the bed. I get calls all the time from people asking for a queen or king size blanket. A blanket that large weighs over 30 pounds and needs to be taken to a Laundromat with industrial size machines.

A removable duvet cover is a bad choice. You have to unzip the cover. Untie the inner liner. Machine was and dry the cover. Hand wash and hang dry the inner liner. Re-tie. Then re-zip. I get many calls from consumers who have learned this the hard way and now want something that can go right in the washer, right in the dryer and then right on the bed.

Is there a warranty that guarantees quality? Because most of the weighted blankets on the market today are made cheaply overseas, there is little or no assurance of quality. We have a lifetime warranty and I can count on one hand the number of blankets that have been returned faulty to us.

All weighted blankets retain some degree of body heat. When weighted blankets exploded on the market in 2017, one of the biggest complaints from the general market was that they were hot. So manufacturers started coming up with alternative covers that were “cooler.” Yes, they will be “cooler” for one simple reason, they are more breathable. Cotton and cotton flannel are “cooler” fabrics because they are more breathable. Heat can more easily pass through than a chenille or minky or fleece. But many manufacturers want prospective customers to think that they will be cool under one of these blankets. But the truth is a weighted blanket presses down on the body and traps body heat. It is going to be 98 degrees. With cotton or another type of cooling fabric it will technically be cooler but most people will not feel a great amount of difference. I always tell people to give their bodies a couple of weeks to get used to the blanket, including used to the added heat.

Paying a little more for our professionally American made weighted blanket is worth it. Our blankets last a long time.

Bevoya: Is there anything else I've neglected to ask you that you want to share?

Photo of the Charcoal Grey Chenille ($ 171.00)

Keith: No, I think this covers a lot. But I do hope the one takeaway will be that after the mass media hype about weighted blanket fades, the fact that weighted blankets have been bringing calm and comfort for over 26 years means they aren’t just another fad, like the Snuggie. Remember those? When I first came up with the weighted blanket idea, there was a similar product called the Slanket. It was a blanket with sleeves invented by a college kid and his mom made the first prototype. He and I both started our businesses around the same time, 1998. Then years later, a competitor came out with the Snuggie and it exploded on the market. But is was a gimmick and a fad, and Snuggies aren’t really around anymore. My hope is that weighted blankets bring calm and comfort to everyone for many more years to come.

The Ultimate Stress Relief Cheat Sheet

An honest recounting of what’s working for me based on personal experience.

If you can stop your nervous system from trying protect you, you can lessen your pain and quell your anxiety.

Hello reader! I’m Meredith Arthur. I work as a Chief of Staff for Pinterest’s product incubation studio and am the founder of Beautiful Voyager, a content and community site for overthinkers, people pleasers, and perfectionists.

I first started my journey into mental health research in 2015 when the neurologist treating my migraines diagnosed me with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. At the time, I found the Google results for “what is an anxiety disorder?” sorely lacking and I created Beautiful Voyager to fill the gap. My curiosity only deepened as I asked the same question over and over: Why didn’t I ever know that anxiety was contributing to the terrible physical symptoms (migraines, nausea, fainting, back pain, cramping) I was experiencing?

In 2016 I expanded my research by taking over the editor-in-chief role for Medium’s largest mental health publication, editing hundreds of personal mental health essays from people around the world. In 2020, just three months into the COVID pandemic, I published my first book on anxiety. That same year, I started working on the nonprofit How We Feel app with Ben Silbermann and Dr Marc Brackett. Since then, thanks to my partnership with the Pinterest social impact team, I’ve gotten to know the founders of many mental health nonprofits and stayed close to new trends in the space. It’s an ongoing journey that I find fascinating both on a personal level and a societal one.

Why a stress relief cheat sheet?

My understanding of anxiety has changed radically over the past nine years of curious investigation. I’ve explored many schools of thought and approaches to anxiety treatment. Take a look at how my answers to the questions “Why didn’t I know that I was suffering from anxiety?” and “Is anxiety connected to the terrible physical symptoms I’m experiencing?” have evolved over time:

2015: I don’t care why I didn’t know. I want to know why the therapists I saw didn’t know.

2017: Seems like, in the field of mental health, you need to know what’s wrong with you for people to be able to help you. At least I have Lexapro now.

2019: I guess I hid it so well that I unintentionally hid it from myself? I still have physical symptoms. I continue to be grateful for Lexapro, which helps me turn down the thermostat on my internal environment, especially on anxious mornings.

2021: I am still really sick—nausea, muscle aches, migraines, lightheadedness. Is anxiety connected to the physical pain I am in? I still don’t get it. COVID hasn’t helped.

2023: After a year spent in bed, something finally helped: I had a hysterectomy. I’m grateful to see a decrease in my physical symptoms, but I am still in pain. I don’t know what to do next. I suspect my nervous system plays a role here.

2024: I finally get it —I have spent a lifetime in a state of nervous system dysregulation. I believe I can improve my physical and mental health by regulating my nervous system. My pain is diminishing. It’s a daily practice, but I am healing.

I’m writing this cheat sheet to help you skip some of the steps I labored through over the years. Everything I share here is an honest recounting of what’s working for me based on personal experience.

Who you are

If you’re reading this, I’m assuming you’re a fellow voyager, a curious overthinker learning to navigate the choppy waters of stress and anxiety from other wayfaring overthinkers.

The philosophy behind this cheat sheet

If you can stop your nervous system from clumsily trying protect you, you can lessen your pain and quell your anxiety. Teaching yourself that you are safe is where this work begins. It’s as hard as it sounds. Your nervous system’s off switch is buried within a sea of internal confusion. (I’m simplifying the nervous system here — there’s no simple on and off switch. Your nervous system is more like fancy LED lights. The switch allows you to change the color and flashing patterns of the lights so that you can give yourself the right lights at the right time. No one needs fluorescent disco lights at 9 AM on a Monday morning. )

To become skillful at using the switch, you must find a path through the internal cacophony and learn which part of yourself to listen to when. A great place to start is with actionable nervous system regulation tactics.

Let’s get started.

Every technique I’m including has the same goal: to teach your body that you are safe. The best approach to all nervous system regulation is “little and often.” In other words, these are exercises that you can do in the moment to send messages of safety to your body (which, in turn, will send them to your mind and help you feel better overall).

Start with foundational, everyday practices.

If you start reading about nervous system regulation, it won’t be long until you start hearing about the “window of tolerance.” Your window of tolerance is, quite simply, your ability to tolerate the challenges of daily life. It’s your body’s ability to move from a hyper-aroused (fight or flight) or hypo-aroused (withdrawn, frozen) back to a more grounded self and place. If you’re interested in learning more about these three states, a great place to start is Stanley Rosenburg’s book on polyvagal theory. These daily practices build your window of tolerance so that you can recover more quickly and easily from nervous system arousal. (The nervous system exists to protect us. It is doing its job by going into an aroused state. The goal is to build a window of tolerance that lets you handle these inevitable daily stressors gracefully and intentionally, without your system being hijacked without you knowing it.)

1. Somatics

I’ve come to think of my daily somatic practice as meditation with movement. Every morning I unroll my yoga mat and follow one of Sarah Warren’s online classes, usually first thing in the morning, in order to release muscle tension and teach my body what relaxed is supposed to feel like. I recommend starting with her level one course. It is a guided experience that builds upon itself every day, costs $45, and take two months to complete. It takes around 20-30 minutes a day.

2. Polyvagal exercises

I bundle the following three lateral eye-movement exercises with my morning practice. They are adapted from Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve by Stanley Rosenberg. Critics will tell you that we don’t yet understand the mechanism that makes this kind of exercise work, warning you to sidestep the hype. While I support a healthy dose of skepticism in all wellness endeavors, it doesn’t hurt you to give them a try as they are easy and totally free. I’ve definitely found them helpful for releasing my trapezius muscle and easing my morning anxiety.

The Basic Exercise

Sit tall wherever you are.

Interlace your hands and clasp the back of your head between your ears, sending your amygdala a message of safety.

With your EYES ONLY, look to the right and hold.

Breathe, relax, and allow your body to soften.

Hold 30-60 seconds until you yawn or feel an internal shift. It can take practice to learn to feel this shift, but the yawn is a dead giveaway that this is working.

Repeat on the left side.

Seated Salamander Exercise

I like to do this exercise on my heads and knees so that gravity helps me breath out with my belly. You can also do it sitting up. Whatever works for you to get the release.

With your EYES ONLY, look to the right and hold.

Allow your right ear to melt towards the right shoulder (not turning your head).

Breathe, relax, allow your head to be heavy and you body to soften.

Hold 30-60 seconds until you yawn or feel an internal shift. It can take practice to learn to feel this shift, but the yawn is a dead giveaway that this is working.

Repeat on the left side.

Sphinx with Head Turn

Lay on your belly and prop yourself up on your elbows with your chest and head facing forward.

Anchor your pelvis by pressing down through the pubic bone.

Draw your shoulders down out of your ears and extend your neck naturally (don’t look up too much).

Turn your head to look over your right shoulder and hold for 1 minute. Again, ou are looking for that yawn or internal shift into ease.

Repeat exercise looking over left shoulder.

3. Brecka breath

I do this practice every morning as part of my somatics/polyvagal routine. It was recommended by a somatic teacher who said, “It may look and feel a bit bro-y, but if you are oxygen-deprived due to stomach gripping or tension myositis syndrome, this kind of breathing can help you.”

What separates this practice from others, as far as I can tell, is the intentional pause you take between rounds of breath. In this special pause you relax and tune into the sounds of the world around you. Stay in that space for a few beats before slowly inhaling, exhaling, then returning to the next round. It took me a while to catch the hang of it, but now I really love that pause.

How to Brecka breathe

When just getting started, do 3 rounds of 10 breaths.

Inhale deeply as shown in the video. Exhale naturally. Do this breath 10 times in a row.

Let your shoulders rise as you breathe in. Fill your chest and belly on the inhale. Allow the exhale to follow the inhale without overthinking it.

Once you have finishes one round of 10 breaths, pause on the inhale. Do not exhale.

Tune into the sounds around you and try not to tense up as you hold the breath. Relax into the feeling. Check out the video to see what this looks like.

Once you’ve held that inhale as long as you can, slowly inhale and exhale, then get ready for round two.

Do another round of 10 breaths, same as above, then pause again on the inhale.

Repeat one last time.

Over time, build to 3 rounds of 30 breaths.

4. Mindset/emotion check-in

Every day I set aside at least 10 minutes to “tidy” my mindset. Depending on the day, I do this by journaling or sitting quietly in the sun. The goal is the same — to create the internal space to understand what’s happening that day on a deeper emotional level.

I use Nicole Sachs’ approach to journaling. It’s called Journal Speak. When you sit down to Journal Speak, your goal is to speak directly from the emotion itself, unmediated by thought or analysis. This is radically different from the way I journaled throughout my 20s, which was filled with overthinking and self-analysis. Remember, many of us unintentionally suppress and avoid emotions we perceive as negative. When we give voice to unconscious negative emotions, we’re defanging them and soothing our nervous systems.

When I’m not in the right place to journal, I do this same practice without paper, sitting quietly in the sun to tune into the negative chatter in my head. I try to feel the emotions surfacing in my body. I allow myself to rest in uncomfortable emotional spaces. This is not easy but I know that it’s important: By teaching myself emotions aren’t as scary as they seem, I am regaining control of my nervous system’s master switch. Once I’ve done that enough, I send soothing mantras/phrases to the parts of my internal self that are complaining the loudest.

5. Afternoon gear shift

Nervous system regulation is best practiced in small and frequent ways. It’s important to learn to shift gears periodically throughout the work day — moving from the sympathetic part of the system (“flight or fight”) to the ventral (“safety and connection”).

Learning to relax in between tasks is another way of mastering your nervous system’s light switch.5 I do this by taking a quick moment in the middle of the day to connect with nature. This could be 5 minutes spent in my backyard, a small walk up and down the street examining tree leaves, or sitting and petting my dogs. I tell myself, “It’s OK to coast sometimes. I don’t always need to be in overdrive.”

I’m a broken record but will say one more time: the goal is to teach yourself that you are safe. If you are able to do that, your entire system can relax, your pain will be lessened, and your anxiety will plummet.

Exercises for difficult moments

Everyday practices are great, but what should you do when you’re facing something hard? Ground, Orient, Resource.

Ground yourself by becoming aware of your feet on the ground or the seat under you. Orient yourself by selecting five things in your immediate environment to focus on, spotting details like color, form, and texture. Resource yourself by finding a small action that tells your nervous system you are safe. If any of these exercises resonate with you, they can act as your resources when you need them.

1. In-the-moment mantra

Too often overthinkers want to fix everything at once, and while that is a nice idea, it’s not always realistic. Having a phrase or mantra you say to yourself is a way to shift your mindset in the moment when you need it.

What makes a good mantra

It has to be a phrase you truly believe — your nervous system will know if you’re faking it

It should be powerful enough to interrupt unproductive or negative thinking

It should be connected to a topic that tends to cause you stress

Examples of mantras I currently use

“I am allowed to have a vacation from [insert issue].”

“I know that future me has [insert issue] covered, so I am going to let this go for now.”

“If I keep thinking this way, I will only get sicker. Instead, I am going to imagine a future in which I’ve solved [insert issue]. I will envision this future in detail and allow that feeling of peace to wash over me.”

2. Belly breathing

If you are a stomach gripper, this is a crucial exercise for your nervous system. Most belly breathing exercises tell you to push your belly out when you inhale. That description never worked for me — I didn’t understand it mechanically. Instead, I have taught myself to visualize the diaphragm in order to understand the mechanics of the breath.

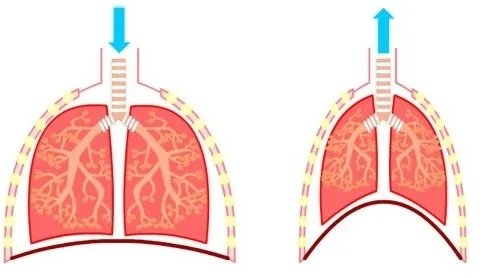

Your diaphragm is a muscle below your lungs, represented here with a dark red line.

Think of your diaphragm as an upside-down-bowl that turns into a plate as it contracts, sucking air into the lungs via the vacuum it creates as it pushes itself flat. Since this muscle pushes down on the top of your belly as air enters your lungs, your belly sticks out. After inhaling, you allow your diaphragm to relax back into its upside-down bowl and naturally exhale. Belly breathing is not about pushing your belly out. It’s about allowing your diaphragm to contract (inhale, think of the diaphragm as flat plate pushing down) then relax (exhale, the diaphragm returns to its upside-down bowl state).

How to belly breathe when faced with stressful situation

Start by releasing all tension in your upper belly. Pop your belly out on purpose to loosen up. Do this in any position, wherever you are.

Next, imagine your diaphragm turning into a flat plate as it pushes down on your belly and you inhale. Your belly now pushes out due to the inhale.

Inhale for a count of 5 or 7. Your belly should feel big and free. Pause for a moment at the top of the inhale.

Now allow your diaphragm-plate to return to its natural curved upside-down bowl state as you exhale. Your belly will go in. Hold on to the feeling of looseness even with the exhale.

3. The Basic Exercise

In addition to being a great foundational practice to build your window of tolerance, this polyvagal exercise is great in the moment when you’re feeling stress.

Sit tall wherever you are.

Interlace your hands and clasp the back of your head between your ears, sending your amygdala a message of safety.

With your EYES ONLY, look to the right and hold.

Breathe, relax, and allow your body to soften.

Hold 30-60 seconds until you yawn or feel an internal shift. It can take practice to learn to feel this shift, but the yawn is a dead giveaway that this is working.

Repeat on the left side.

4. Neck massage using oil

This one is simple — I take a few drops of this scented vagus nerve scented oil and rub my neck and ears with it. I spend a couple of minutes trying to release tension in the sides of my neck and follow the patterns recommended for my specific migraine pattern as illustrated in Stanley Rosenberg’s book.

Whew, that’s a lot!

If you’re still reading this, good work. This stuff is not easy. Whether you’re at the beginning of your journey or a seasoned mindbody traveler, I would love to hear from you. Write me in the comments and let’s help each other along the way.

Recommended Reading

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren

Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve: Self-Help Exercises for Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, and Autism by Stanley Rosenberg

The Mindbody Prescription by Dr John Sarno

Recommended Listening

The Cure for Chronic Pain Podcast with Nicole Sachs

SOMA: Releasing Muscle Tension and Reliving Chronic Pain with Clinical Somatics Podcast with Sarah Warren

Using Polyvagal Theory to Balance the Nervous System on The Adult Chair Podcast with Michelle Chalfant

All About the Vagus Nerve

Fascinating research about the role of the vagus nerve in regulating emotions and improving our feelings of connectedness (and wellbeing).

Photo by Basil James

In the past three months, my understanding of how to navigate my dysregulated nervous system has been super-charged through my learnings about polyvagal theory and the inner workings of the vagus nerve. I read Stanley Rosenberg’s step-by-step book on the topic and met regularly with an incredible somatic educator / coach, Amanda Joyce, who has helped me put the pieces together in a new way. Amanda shared a page of her own notes about the vagus nerve with me, and I organized them into the sections you see below. I encourage you to dig into this summary, but then go deeper with Rosenberg’s book if you have the bandwidth. It is pretty mind-blowing stuff. Even though we still don’t understand all of the mechanisms of the vagus nerve, we understand a lot more than we used to, and this information can be a gamechanger for overthinkers who learn to harness its healing power.

What is the vagus nerve?

The Latin meaning of vagus is “wanderer”

Discovered in past two decades

Allows for understanding of others' emotions

Controls muscles for facial expression

Displays emotions on faces and in voices

Regulates basic functions like breathing, heartbeat, and eye dilation

Plays role in sleep, mood, pain, stress, and hunger

Largest nerve in the body’s autonomic nervous system

Connects brain to large intestine

Controls muscle movement in body

Innervates trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles

The vagal pathway bi-directional: 80% information from body to brain, 20% information from brain to body

Communicates gut information to brain using neurotransmitters and hormones

Responsible for receiving and spreading the message that you are safe, so it can restore regular functions, and you can relax.

The connection of your vagus nerve to your brainstem is different from being connected to your thinking brain. There is only one language the brainstem speaks: Am I safe, or am I unsafe?

It receives fight, flee, or freeze messages from your brainstem (lizard brain) and help the rest of your body prepare to engage in a survival response.

Through your brainstem, your vagus nerve — along with the cranial nerves responsible for senses like sight and hearing — scan both your internal and external environments for safety and danger.

An important part of our body's control system is known as the "vagal brake" which is a system that helps regulate your heart rate and breathing. It's like the brakes on a bicycle that help you go faster or slower when needed and gives you the right amount of energy for each moment.

To understand polyvagal theory, you must first understand the relationship of the neck to the head

The complicated coordination of tension and relaxation of the muscles that turn our heads requires precise muscle control. This is programmed into our nervous system in such a way that we do not have to think about the mechanics of it.

When something catches our attention, we automatically focus our eyes on it. The movement of our head follows the direction of our eyes, and then the movement of our body follows the movement of our head.

Turning the head is one of the most important and complex movements of the body. As babies, it is one of the first movements we make. Control and coordination of the tensing and relaxation of these muscles depend on well-functioning cranial nerves.

Turning the head to either side should be an even, well-coordinated movement, without stops or jerks and without deviation from a smooth curve. Ideally, the head should be able to turn ninety degrees or slightly more.

With chronic tension or flaccidness of these muscles, we obtain a forward head posture which reduces our breathing capacity which also means increasing anxiety, general fatigue, and low energy levels.

Forward head posture also puts pressure on the heart and crowds the blood vessels that go to and from the heart while compressing the vertebral arteries that carry blood up to the head, diminishing blood supply to the face, parts of the brain, and the brainstem.

What is polyvagal theory?

Presented by Stephen Porges in 1994, polyvagal theory is a model that describes the role the vagus nerve plays in regulating emotions, fear responses, and social connections. It identifies social engagement as a type of nervous system response.

Social engagement is a playful mixture of activation and calming that operates out of unique nerve influence.

The social engagement system is a two-way interaction system (receptive and expressive) based mainly in the eyes, ears, larynx, and mouth but incorporating the entire face and the torso above the diaphragm. All twelve cranial nerves participate in the social and expressive functions.

Social engagement is the human neurobiological network that is accessed when you feel safe, which facilitates connection/affiliation with others and your surrounding environment through eye contact, facial expressions, vocalization, and orienting of the body/face toward others.

The social engagement system helps us navigate relationships. Social engagement forms the basis of social relationships by providing a sense of belonging, social identity, and fulfillment. Spending more time in the social engagement state of the nervous system is associated with positive health behaviors, and improved communication and social skills.

Social engagement is not a fixed or permanent state. If you have experienced an imbalance of time spent not in this state, then repeat balancing techniques should be done frequently or at least as needed. Since there is no such thing as a fixed state of balance, it is more useful to think of balance as an ongoing process.

Societal expectations pressure you to feel as though you should appear calm and in control at all times. However, this is not how nervous systems work and does a disservice to honoring the importance and value of the other nervous system states and their many hybrids.

Ventral vagal is safe and social (that is our connected state); you have the sympathetic, which is fight-or-flight; and the dorsal vaga- shut down or freeze. also have hybrid states

What the role of human connection to the nervous system?

The human brain and our entire being (whether in children or adults) are designed for connection with a deep desire to be felt by others. We all need to be seen, valued, and met within our relationships.

Regulating your nervous system does not mean becoming calm; it means becoming connected.

Regulated or connected means having the ability to hold mindful awareness of whatever emotions you are experiencing while maintaining access to higher centers of the brain to remain grounded and connected in order to make decisions and respond.

You can be angry and still connected to yourself.

When we show up in relationships with the intent to be present with another person, it can sometimes look messy rather than calm in its presentation.

When “messy” is authentic and connected, and therefore regulated, even those moments can ultimately have the impact of repair, reconnection, and security.

The foundational trinity for connection is grounding, orienting, and resourcing.

GROUNDING is coming down to earth, feeling our bodies in relationship to the ground beneath us. Feel feet on the floor, butt in chair, etc.

ORIENTING is the process of becoming aware of our location in time and space- count colors, soft/loud sounds both ears, smells around room, taste in mouth, feelings touching your body

RESOURCING refers to accessing our resources- could be sensations, emotions, colors, places, people, sounds, animals, types of music, places in nature, activities, animals, or people, symbols, words, concepts, archetypes, or figures— anything that shifts your state in a positive direction toward a sense of well-being, safety, gratitude, grounding, compassion, empowerment, or inspiration.

Building the “window of tolerance”

A window of tolerance is the range of nervous system arousal you can tolerate without becoming overwhelmed and either hyper or hypo-aroused.

Stressors, both good and bad can still occur when you're within this window, but you are better able to tolerate the discomfort, and you're able to respond instead of simply reacting if you have good vagal tone

It is neurobiologically and behaviorally possible to be highly aroused and still be regulated and contained within one’s window of tolerance. Discerning the difference between regulated activation of emotions as information and triggered states of emotional dysregulation that lie beneath awareness is a critical distinction.

If you're feeling anxious and want to calm down, concentrate on your exhale. If you're feeling stuck and want to become more alert, focus on your inhale.

Emotional metabolism

Here is what we know: what appears to arise from the mind might actually be being caused by the body, and looking after the body is, therefore, key to looking after the mind.

When your nervous system is overwhelmed, your neocortex goes offline, which means you can neither take care of yourself as you operate in real-time nor integrate any new skills. This is why when you are overwhelmed (reptilian brain running the show), you are not logical or rational (traits found in the neocortex).

Pendulating is a term that describes the natural rhythm of contraction and expansion within our bodies. Think of it as the natural flow of breathing in and out.

Understanding and experiencing this rhythm reminds us that even when we're going through tough times, there will be relief.

Using pendulation has begun the deep work of getting to know your nervous system states and tracking your sensations, which will guide you to understanding what yes, no, and maybe feels like inside your body- connecting to your intuition.

This work will help you build resilience, choose clean pain, and train your nervous system to shift flexibly to different states as needed. Using your vagal brake, keeping your neocortex online, and metabolizing emotions will help you find freedom inside your body as well as your life.

And just like any muscle you are working to tone, it takes consistent training. Knowing the information and waiting until you are in desperate need of the tools will make it incredibly difficult to implement them.

As you become more confident in your ability to stay grounded and in control, you can consciously adjust the balance towards calm when anxiety rises or towards heightened readiness when you need to take action.

If you speak rationale to someone overwhelmed, you may as well be speaking another language. Think of that time you lost it (hyperarousal) only to later think, Okay, maybe I overreacted. Though at the time it absolutely did not feel like you were overreacting.

Exploring the Vagal Brake

The vagal brake affects your breathing rhythm. It slows down your heart rate to keep it within a healthy range (between 60 and 80 beats per minute).

When you breathe in, the brake eases up a bit and your heart beats a little faster. When you breathe out, the brake engages and your heart rate slows down again.

It's like gently squeezing and releasing the bicycle brakes. Focus on extending your exhale, which engages the brake slightly and helps calm your system.

Picture yourself with one foot in a state of social engagement and the other foot in a mode of heightened readiness, like preparing to take action. Shift your weight between them, swaying slightly from one foot to the other.

Inhale as you lean towards the foot associated with heightened readiness, and then exhale as you shift your weight back to the foot associated with social engagement. Do this for a few breath cycles to feel the rhythm of your "vagal brake" releasing and re-engaging.

As the vagal brake releases, you'll notice a range of responses becoming available. You may feel engaged, joyful, excited, passionate, playful, attentive, alert, and vigilant, all while remaining within the boundaries of safety and social connection provided by the ventral vagal system.

Without this vagal brake, we risk losing our sense of safety and connection and can easily slip into the protective states of fight-or-flight.

Experiment with pushing the limits of this release.

Shift your weight in such a way that you're almost entirely leaning towards heightened readiness. Notice how your balance starts to shift and you might feel less steady. Then, return to a solid base by shifting your weight back to the foot anchored in social engagement.

Try the opposite too, with most of your weight on the foot connected to social engagement, and just a light touch on the other foot associated with heightened readiness. Observe the changes in your experience.

Experiment with how your vagal brake allows you to gather and mobilize energy and then helps you return to a state of calm.

Recognize how the vagal brake serves as a boundary between the safety and regulation of social engagement and the survival response of heightened readiness.

Once you've grasped the concept of your vagal brake, you can start playing with adjusting the balance between energy and calm deliberately.

Practice maintaining your anchor in safety while experiencing mobilization. Alternate between periods of rest and taking action.

Explore the full range of experiences that emerge as you release and re-engage your vagal brake.

Think about situations in your daily life where you either need to be energized or calm, and consider how you can use your vagal brake to help you navigate those moments effectively.

Recall a situation where you needed more energy and visualize yourself releasing the brake to meet that need. Then, bring to mind a moment when you wanted to feel more relaxed and re-engage your brake to achieve that sense of ease. You can use past experiences as a reference and play around with the idea of releasing and re-engaging your vagal brake to imagine how the right balance of energy might have changed those situations.

That’s it for the notes…for now. More coming soon, I’m sure.

Three Vagus Nerve Reset Exercises

In my latest Substack post I mention three polyvagal exercises I’ve been doing regularly to reset my nervous system…

In my latest Substack post I mention three polyvagal exercises I’ve been doing regularly to reset my nervous system. I wanted to share the details of those exercises here in case they help you, too.

The Basics Exercise

Sit tall in a chair (or toilet! That can be a good way to remember to do it!)

Interlace your hands behind your head. Sit tall.

With your EYES ONLY, look to the right and hold.

Breathe, relax, and allow your body to soften.

Hold 30-60 seconds or until you feel a deep relaxation.

Repeat on the left side.

Seated Salamander Exercise

Sit tall in a chair (or toilet! That can be a good way to remember to do it!)

With your EYES ONLY, look to the right and hold.

Allow your right ear to melt towards the right shoulder (not turning your head).

Breathe, relax, allow your head to be heavy and you body to soften.

Hold 30-60 seconds or until you feel a deep relaxation.

Repeat on the left side.

Sphinx with Head Turn

Lay on your belly and prop yourself up on your elbows.

Anchor your pelvis by pressing down through the pubic bone.

Draw shoulders down out of your ears and extend your neck naturally (don’t look up too high).

Turn your head to look over your right shoulder and hold for 1 minute, switch.

A Clinical Somatics Q&A

A Q&A with Sarah Warren about her work bringing Thomas Hanna’s clinical somatics to the wider world

Photo by Charlotte Karlsen

Clinical Somatics changed my life and it might yours, too.

When I find something that works, I am not shy about it. That’s why I’ve been shouting from the rooftops about Sarah Warren and her work bringing Thomas Hanna’s clinical somatics to the wider world via through her book and online courses. In this Q&A I get the chance to ask Sarah the questions I’ve had since first starting my clinical somatics practice. Two reasons to be thankful for our digital age: access to new information and the ability to connect with the people who inspire you! Thank you, Sarah, for taking the time to share everything you’ve learned with me and with voyagers everywhere!

Bevoya: Sarah, I am so grateful to you for your work bringing Clinical Somatics to me in an accessible, intuitive, day-by-day format. I have been researching mindbody approaches to healing pain for years and never found an approach to help me reset my nervous system and release muscle tension like yours. Why do you think it is that this kind of healing is so hard to find?

Sarah Warren: I believe the main reason why Clinical Somatics isn't more well-known is that Thomas Hanna, the man who developed the method, died in a car accident at a relatively young age. He had just started teaching his first professional training, so when he passed away there were 38 practitioners who were only partially trained. His widow, Eleanor Criswell, continued to teach, and these 38 practitioners worked with Hanna's long waiting list of clients. Hanna was a passionate, charismatic teacher with a dedicated following. People would travel across the country to have sessions with him and attend his workshops. But when he passed away, the momentum he had created slowed way down. I'm certain that if he had been able to live to old age, Clinical Somatics would be very well-known.

Thinking of Thomas Hanna, pictured here, with gratitude (and some sadness)

Thank you for your pioneering work,Thomas Hanna!

The other reason why Clinical Somatics and other types of self-care aren't more mainstream is that in our society, we've been taught to let doctors and other health professionals make decisions about our health. We grow up thinking that they are the experts in our personal health. Now, Western medicine is truly incredible in some ways, especially in life-threatening situations. But when it comes to chronic health conditions that are caused by lifestyle, visiting a practitioner of Western medicine is fairly useless. We need to make changes in how we're moving, eating, sleeping, dealing with stress, etc. We need to take responsibility for our own health. Most people haven't grown up expecting to have to do this, so it can take a big shift for people to be willing to really take the reins when it comes to their health. And it may take time, patience, and a lot of exploration to find the right solutions for their unique health situation. But, speaking from personal experience, it is so worth it! For any of your readers who aren't familiar with somatic movement, this video and article are a good introduction.

Bevoya: In your years of doing this work, who do you think is most likely to benefit from the Clinical Somatics approach? Is it a coincidence that I am an overthinker with lifelong migraines and neck pain whose back pain really kicked up in the past couple of years? Is this the kind of story you hear frequently?

Sarah Warren: The type of chronic pain that is relieved by Clinical Somatics is musculoskeletal pain caused by chronic muscle tension. The majority of chronic pain cases fall into this category, but certainly not all. Tight muscles themselves are sore and painful. They pull our connective tissues tight, leading to tendinitis and ligament sprains. They pull our skeleton out of alignment, leading to joint degeneration. Misalignment of our skeleton puts pressure on nerves, leading to nerve pain. So, the underlying cause of most musculoskeletal pain is functional—chronically tight muscles—but the end result might be a structural issue, like a herniated disc or cartilage that has worn away.

So, people whose pain falls into that category are those who will benefit from Clinical Somatics. But on top of that, people need to be willing to slow down and take some time each day to lie down and practice the exercises. This is very hard for some people! Some folks really struggle to do the very slow exercises and focus on what they're feeling in their body, because they're used to moving quickly and having an external focus. These tend to be the Type A “go-getters.” I get quite a few emails from these students who report that at the beginning of their learning process they had a really hard time, then as the weeks and months went on, they gradually got comfortable with slowing down and focusing on their internal sensations. And then a whole new world opened up to them. I love getting those emails!

Bevoya: I found and bought your book and online exercises out of desperation after I had tried everything else to improve the iliopsoas tendinopathy I was diagnosed with. So many physical therapist appointments, and my next step was about to be more x rays and a corticosteroid shot to the hip...and none of it was helping. I am three weeks into your program and the improvement is significant. More than that, I am living differently in my body. In particular, I am relaxing my belly muscles more frequently during the day and doing diaphragmatic breathing. What are some of the specific things that other people say they notice about how their body changes after Clinical Somatics?

Sarah Warren: There are so many positive changes that people experience! The most common reason people come to Clinical Somatics is for pain relief, and that's what I focus on in my practice, so that's what I hear about most often from students. Muscle tension relief and improved posture are also inevitable if you practice the exercises regularly. Stress relief, better breathing, better sleep. The ability to return to activities and workouts that they love to do but couldn't because of their pain. A new relationship with their body, with heightened sensation and awareness throughout their body. The ability to quickly and easily get themselves out of pain if a new or old pain arises. Increased empathy, patience, and enjoyment of their daily lives. And, since we hold psychological tension in our bodies as muscle tension, some people report the release of longheld emotional stress and trauma.

Sarah Warren demonstrating the One-sided Arch & Curl. The key to clinical somatics exercises is to move slowly and stay attuned to the muscle group you’re engaging as you go.

Bevoya: What are some things that Clinical Somatics can't help with? For example, I have Achilles tendinitis in my right ankle. I assume that this will not be improved by Clinical Somatics. Is that true? In response to my newsletter, a friend wrote "It looks like the exercises are centered on helping with back and torso pain, which my probs are more in my feet and knees... I wonder if maybe those would be helped residually, though?"

Sarah Warren: Clinical Somatics works with the entire body, and can definitely relieve Achilles tendinitis and other issues in the extremities of the body. Posture and movement patterns begin in the core of the body—our core is like the foundation of a house. If there is muscle tension or misalignment in the core of our body, it affects our entire body. Often, an issue in the core of the body is actually felt in our extremities, so we think that's where the problem is. For example, let's say you're hiking one hip up higher than the other (functional leg length discrepancy). That's an issue in the core of your body: your waist muscles and lower back muscles are tight, hiking your hip up. But you may only feel pain in one of your knees, because your weight is shifted to that side, putting an unnatural amount of pressure and strain on that knee. No amount of therapy focused on that knee is going to solve the underlying problem, which is the fact that your hips are out of alignment. So in Clinical Somatics, we always start by working with the core of the body so that we can address foundational issues. Then as the learning process continues, we introduce more movements that work with the extremities. Regarding your Achilles tendinitis, you can read my article on tendinitis to learn about the full-body patterns of tension that are typically involved. And in answer to the first part of your question: Yes, there are some types of pain that Clinical Somatics doesn't address. Basically, any type of pain that isn't caused by chronic muscle tension or habitual body use. For example, pain resulting from peripheral neuropathy, which is most often caused by diabetes, infections, or exposure to toxins. Another example is painful autoimmune conditions; the pain in these conditions is caused by inflammation, so the cause of the autoimmune condition needs to be addressed. This often involves a combination of factors like diet, stress, infections, and exposure to toxins. Chronic pain can also be neuroplastic in nature, meaning that the nervous system adapts by making your pain increase over time. Pain receptors become more sensitive, the spinal cord becomes more responsive to pain signals, and more neurons in the brain are recruited to respond to pain signals. I write about that type of pain in this article.

Sarah Warren demonstrates the One-sided Arch & Curl from another angle. One of the things I love about her approach is how detailed it is. Sarah shares the level of information I need to understand and learn!

Bevoya: What is your vision for this work in the future? Do you have a dream about how ClinicalSomatics will be incorporated into medical fields or as treatments suggested by doctors? Are there obstacles to that?

Sarah Warren: Yes, in an ideal world, doctors would refer their patients to Clinical Somatics in the same way they currently refer them to physical therapy. That would be amazing! I believe we'll get there, but there are some obstacles. Clinical Somatics isn't currently covered by health insurance, so that's a big obstacle. Before that can happen, the Somatics community (which includes Clinical Somatic Educators and Hanna Somatic Educators) needs to come together to form an organization that includes certified practitioners from all the major training programs. There must be guidelines put in place to ensure that the training programs are all teaching the same basic information. Once this organization is in place, I believe the next step would be introducing licensure for Clinical Somatics and Hanna Somatics practitioners. Once we have this type of regulation in place for how Clinical/Hanna Somatics is practiced, then we could pursue getting covered by insurance. Going back to my answer to your first question: I believe we'd be much farther along in this process if Thomas Hanna hadn't passed away.

Regarding my personal approach: I don't have much patience for dealing with institutions. At the moment, I feel like trying to introduce Clinical Somatics into mainstream medicine would just slow down my efforts. I really enjoy going straight to the people who need it, and making Clinical Somatics accessible for them. I've always felt like this is my role. When I first learned about Clinical Somatics, I felt like most people do—why doesn't everyone know about this? In addition to the reasons I already listed, another reason is that “what Clinical Somatics is” can be a tough thing to communicate. We use words like “pandiculate” and “sensorimotor awareness” that people have never heard. We talk about the stretch reflex (myotatic reflex) and the gamma feedback loop, and tell people not to do static stretching—the opposite of what they've been told their entire life!

My passion has always been: How can I communicate what Clinical Somatics is in a really clear, simple way so that people understand how they can benefit from it? So, that's what I strive to do every day through my website and my courses. I wish that literally every human being could practice Clinical Somatics. Can you imagine what a wonderful world that would be? There would be a dramatic reduction in chronic pain, and associated problems like depression. There would be a reduction in opioid prescription, abuse, and related deaths. There would be a vast reduction in elective orthopedic surgeries, like hip and knee replacements. Not to mention reduced healthcare costs! And, people could be more physically active as they age, would would extend their lives and improve the quality of their lives. It may sound a bit crazy to say that all of these effects would result from everyone practicing Clinical Somatics, but once you do it for yourself and experience the benefits, you know it's true.